Myths Around Ergonomics And Workplace Design

Ergonomics- a vital study of human use of everyday products while reducing risk of injury, maximizing optimum comfort and enabling better performance. Yet, it is a least understood science and it gets beaten somewhere between branding and advertizing. This conversation with Tim Springer, sprung out of one such conversation that I was privileged to have based on treadmill  workstation that have alarmingly been gaining popularity.

workstation that have alarmingly been gaining popularity.

Tim Springer of Hero Inc. with his vast experience of 30+ years on ergonomics and workplace design opens up to explain myths and myth busters around the subject. More than that, he expands his view on history of workplace design, changing technology and its impact and how it possibly is affecting our bodies as we adapt to go around working everyday jobs.

Q. In your long and wide experience as a workplace researcher, what are the

changes that you have observed in the industry in last couple of decades? Tell us a bit about both good and not so good changes that have taken place in this time.

A. Looking back over the 30+ years, from 1970, I’ve been involved in workplace issues, it is apparent that things have changed rather dramatically. [1970s]Herman Miller’s Facilities Management Institute was largely responsible for bringing definition of the role and professional development of the nascent practice. This was a time of rapid, sweeping changes. In the US, the number of white-collar workers surpassed blue-collar workers for the first time around 1980. The personal computer was introduced and rapidly adopted, thus changing the way information was handled. Women were entering the workforce in record numbers. All of which drove the need for more office space and the ability of those workplaces to be adaptable to changing demands.

Since that time I’ve seen four major advances in workplace strategy:

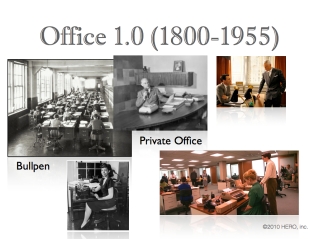

Office 1.0

This is the original dating from the early 1800s. Workplaces are assigned based on status/ Private offices for leadership (usually with windows – the famous “corner office”) and open bullpens for staff. We still find examples of this in some companies.

Office 2.0

The so-called “open office” or office landscape, was introduced in the 1950s. During the 1970s and 1980s the need for office workplaces grew rapidly. Entry of Baby Boomers in office workers, especially an unprecedented number of women, and advances in computing and information technology were all the big changes shaping the workplace. This new wave of white-collar information workers raised the need for workplaces that responded better to change. The explosion in demand for office space drove exponential growth in the commercial real estate industry, information technology and the office furniture industry. One response was the development of the Action Office – Robert Propost’s orginal design of a responsive, multi-tasking work system. Unfortunately, the functional flexibility of the original design devolved into “systems furniture”. Rather than serving the original intent of work settings that were responsive to changing needs and increase flexibility, systems furniture became synonymous with cubicles, universal footprint “cube farms”, and “Dilbert-ville”

There is nothing inherently bad about systems furniture. We’ve seen it used very effectively. Sadly, we have also seen it used far too often as a way to homogenize space solutions and minimize change. Many companies still use this approach.

Office 3.0

During the 1990s the fledgling Internet coupled with the first generation of truly portable technologies merged to serve businesses’ drive toward continually reducing costs. This, in turn, led to experiments with “alternative officing.” The result was progressive reduction in individual workspace, reduced enclosure by lowering partitions, and a variety of ways to use workspaces (e.g., hotelling, hot desking, telecommuting). All of which had one goal – cut real estate costs. Recently – paralleling the economic downturn and financial crises- this approach has gained in popularity and experienced a renaissance.

Without a doubt this is the worst of the four “generations” of office design. It marks the high point in cost consciousness and the low point in creative design. In Office 3.0 both space and people are treated as commodities – a cost to be reduced by any means. It ignores both history and science from which we know space is not neutral but has a positive or negative impact on occupants.

This approach is usually justified by faulty and disingenuous thinking. “The Calculus of Collaboration – goes something like this:

• We need to innovate more.

• So let’s lower all the walls and put more people closer together.

• By being closer together they will experience “social friction”

• Social friction will lead to them communicating more.

• When they communicate more they will collaborate,

• Collaboration will result in innovation.

The idea of people collaborating and innovating simply because they are in closer proximity to their neighbor is a myth.

I have not seen one credible study that supports this logic. In my experience the opposite is true.

Brill (1984) showed the opposite of this thinking. More openness lead to less communication; while more enclosure lead to more collaboration. Brown (2008) showed that all the new trendy design doesn’t increase communication or collaboration. He found the critical issue is proximity to those one needs to work with.

Increased density and reduced enclosure adds to distraction – the number one complaint since the beginning of the office and the number one productivity killer. Sykes (2004) reviewed research dating as far back as 1955 showing “conversational distractions” as the principal deterrent to office performance and productivity.

Finally, if decision makers were honest they would admit that all this discussion about collaboration and teamwork is a false front for the real reason to pursue this approach – cost cutting. It is a short-term approach to a long-term problem. You can’t grow and prosper by cutting back.

Benching, for example, is one of the latest (and worst) variations on this theme. Benching offices bear a striking resemblance to a school cafeteria along with the noise and distraction.

A common lament from businesses is a lack of occupancy in their offices. This should not be a surprise. As technology has become more powerful and portable, people vote with their feet and find truly alternative places in which to work. While these “third places” are seldom good places to work (e.g. coffee shops) they are better than the office their employers provide.

This approach to workplace design can’t die fast enough.

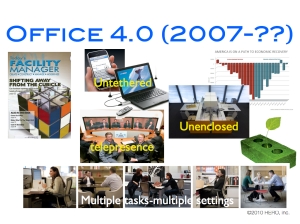

Office 4.0

This is a nascent, but emerging approach. Beginning sometime in 2007-2008, at the height of the most recent financial crises, examples and evidence of rethinking workplace began to emerge. Today, six years later this remains an “emerging” trend. Sadly, it may never be mainstream or widely accepted. But several things distinguish this approach from prior “generations.”

1. Designers and facility managers are finally recognizing that work is not done in just one way or in just one type of setting. It is not well served by “either-or” thinking but requires an approach that embraces “both-and” approaches that support multiple work modes and multiple types of work settings.

2. Technology has become truly portable and untethered enabling more mobility within and between places. For example, telepresence – the ability to use technology to communicate in multiple channels between remote places – has helped workers meet virtually and is reshaping thinking about workplace.

3. Agility – rather than simply flexibility – is beginning to emerge as a design goal. Flexibility as a design goal usually results in trying to be all things to all people resulting in nothing done well. Agility is purposeful adaptation to the immediate need.

Several companies have explored new designs that represent examples of Office 4.0. Microsoft in the Netherlands and a number of Google offices around the world show some elements of Office 4.0, although they also retain the hangover effect of Office 3.0.

The Google Garage may be the clearest example of rethinking workplace. Link here. As Louis Sullivan noted “form ever follows function” and the garage focuses on function and agility more than form.

Q. As an expert on ergonomics and workplace, what kind of points you would like to make and suggest for professionals who are interested in diving deeper to understand this field which often gets hazed by popular trends and fashionable statements in workplace industry.

I’ve often said that the burden those who practice ergonomics carry is when they do their jobs well, solutions seem like common sense. But that doesn’t mean ergonomics is simply applied common sense. I like to describe ergonomics as the science behind the art of human-centered design.

We know a lot about how people interact with and experience their environment and the artifacts in it. Ergonomics applies that knowledge to inform designs of devices and environments so that they work. The HERO Inc. goal is “to make the things people use and places and ways they use them safe, comfortable, easy and effective.”

Ergonomics has its roots in two diverse fields – behavioral science and engineering. It combines what we know about human behavior with the functional design of devices and elements. Today ergonomic research touches on almost every form of human endeavor. Generally, ergonomics falls into two major categories: cognitive ergonomics, dealing with how our brains work, how we make decisions, how we experience the world; and physical ergonomics, the more traditional area of size, shape, and physical features of users, devices and environments.

For those seeking good quality information and expertise in ergonomics, a good place to begin is one the professional organizations. The International Ergonomics Association (IEA) and the US “sister” organization Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (hfes.org) offer a deep and rich set of resources that cover all areas of the field. They publish a number of books and journals as well as lists of consultants and academic programs in the field. Many universities offering degrees in ergonomics or human factors also offer on-line courses and summer programs.

One note of caution, a common issue we deal with is advice or solutions offered by unqualified individuals or firms looking to capitalize on the need for solid ergonomics in workplaces. Not everyone claiming to have ergonomic expertise is well qualified. Often what is offered as science is really poor design and/or marketing wrapped in a thin veneer of data. So, the buyer must be especially aware.

While ergonomics may seem like common sense, it’s not something in which one acquires expertise by reading a few articles or attending one or two workshops. You may gain awareness and understanding but that does not qualify as expertise. Gaining expertise and mastery requires years of study and experience studying and applying ergonomic principles. A minimal requirement is an advanced degree from a recognized and respected university program. Membership in IEA or HFES is also strongly recommended.

Q. There are several myths that have become popular in the design industry and one being which we recently spoke offline about is treadmill workstation. In your experience, what are other such examples that took off based on flimsy grounds of health? How can we rectify such myths to take roots?

A. You’re right. There are several ideas that are trendy, but that doesn’t mean they are legitimate trends. I urge people to look at the science – not the marketing hype.

I mentioned benching earlier. This is a space saving measure not a functional solution. Benching assumes people will resist the natural tendency for establishing boundaries and “magically” work together. Science shows this is fallacy.

An early researcher into human behavior and space, Edward T Hall developed the theory of Proxemics in the 1950s. Essentially Hall’s theory posits that there are zones of space that affect and are influenced by human behavior. The smallest and closest zone is personal space. Benching effectively forces people to allow others to operate at what Hall calls “intimate” distances – where noise (operationally defined as unwanted stimuli) creates maximum distraction.

Researchers have provided evidence that crowding affects behavior negatively. The most extreme examples of crowding studies are called “behavioral sink” studies. Here groups were allowed to adapt to boundaries of space, then the space was reduced by 50%. All sorts of aberrant behavior resulted including violence.

So benching is a bad idea for so many reasons.

You mentioned treadmill desks. This is another trendy idea that not only finds no support from science but actually works against what we know.

First walking on a treadmill is based on the legitimate idea that moving while performing office work is good for you (more on this in a moment). But the claims for benefits of walking on a treadmill while doing information/knowledge work are specious. Treadmills when used as workstations lock people into a forward facing position. Lateral movement is either not at all easy or impossible. The noise of the treadmill is another distraction in an already noisy environment. All of which would be enough to dismiss this idea. However, science – specifically neuroscience and cognitive ergonomics – tell us that engaging to two very different types of activities simultaneously degrades the performance of both tasks. We use very different parts of our brains to walk (gross body movements, tactile sensation, balance, etc.) than when we to do information or knowledge work (higher order cognitive processing, cerebral cortex, decision making, language skills, etc.). Doing both at the same time creates “cognitive dissonance” where the signals going to different parts of the brain interfere with one another. The result is like the description of flexibility as a design goal – we end up doing nothing well.

Real world examples of this can be found in legislation in the US to prevent texting while driving; or London’s Brick Lane where light poles are padded to protect people walking and texting.

Treadmill desks are a bad idea – all you have to do is look at the science rather than the hype.

There have also been several news items about how sitting is bad for us – thus the focus on treadmills and other forms of standing workstations.

First, sitting is no more dangerous than lying down or standing. The risk comes from maintaining constrained postures or positions for long periods of time. Doing so, regardless of the position (standing, lying down or sitting) is bad for you. One of the things technology has done is take jobs that were relatively sedentary and made them even more static. People used to get up regularly and move about the larger workplace to communicate with others, to drop off or pick up documents. With computers all that work that required physical movement is now done electronically. Consequently, we find that people are maintaining the same position for much longer periods of time without much movement. This is bad whether sitting, standing or lying down. Our bodies evolved to move. We need to examine the nature of work and try to design jobs that include alternative activity – preferrably activity that involves larger movement than typing or moving a mouse but doesn’t introduce the cognitive dissonance of which treadmill desks are guilty.

With regard to sitting at work, there have been some notable advances in chair design. Materials and engineering allow designers to create more dynamic machines for sitting that respond to shifts in body center of gravity and adapt to changes in posture and position. See this PDF here.

Sitting is not necessarily dangerous. Sitting too long in constrained positions is. Thus, as with many other things – moderation is the key.

Standing workstations are not new – they have been around for centuries (Thomas Jefferson and Winston Churchill are both famous proponents of standing desks). Standing for brief periods can be a way to relieve stress and engage other muscles. But standing in the same place for long periods of time without relief is not good either.

Other examples:

Display height – As displays got bigger, the height of the display can cause discomfort. Myths include raising the display to be at or above eye height. Similarly, one manufacturer claims displays should be lowered below desk height. Neither is a good practice. A good rule of thumb is the top of the display should be about even with your arm when it is extended directly in front and parallel to the floor. This places the upper right corner of the display (where much of the screen activity takes place) at about 10° below horizontal measured from the eyes. This is the natural area where they eyes look for something in near to middle distance. Our eyes evolved that way. We look up to look for away (“Look, the lions are coming!) we look down to see thing closer to us (“Don’t step on that snake!). So placing something we want to read above 10-15° below horizontal works against this natural behavior. Also, as we age, many people need correction for both near and far vision. Bifocal and trifocal lenses place the reading and middle distance correction in the lower half to third of the lens allowing our eyes to move rather than our heads.

Sinking the display below the work surface introduces all sorts of unexpected consequences. The surface must be transparent in order to see the display. Doing so degrades the quality of the image and often present reflection and glare adding to eye strain. The physical placement causes users to crane their neck forward adding to stress on the shoulders, neck and back. Finally, even with flat panel displays, sinking the display into the work surface takes away valuable knee space forcing increased viewing distances and in some cases obstructing legs and inhibiting lateral movement.

I covered this and other ergonomics myths in this column for Today’s Facility Manager

Q. As a client, who wants to be savvy and informed, what kind of resources you would recommend to them for making sure they are making good decision and investment in making their workplace for their company.

First and foremost, ergonomics is not something you do once. It is a journey, not a destination. It is an approach to providing and managing workplaces that should be

on-going and with time and effort integrated into an organization’s DNA. Getting to that point requires commitment and involvement of various stakeholders in an organization – staff and management; facilities and business units.

Most successful ergonomic programs begin with a committee of users. This group invests the time and resources internally to do the important groundwork. They may decide to hire an objective expert. But effective ergonomic programs always involve an internal group that “owns” the program and processes.

There are many resources available from a variety of sources. The organizations mentioned earlier are a good starting point. Many product vendors offer information as well. However, one must exercise caution in using vendor-provided ergonomic information. Many manufacturers of workplace products make claims about the ergonomics of their designs without valid and reliable supporting research. It is wise to seek outside, objective confirmation.

It’s important to understand work, workers and workplace are elements of a complex system. Unfortunately, in the case of office workplaces the elements are familiar – chair, desk, computer, etc. The complexity lies both in the individual elements and the interaction of the elements.

I often get asked, “if we can change just one thing, what should we change?” A seemingly simple question with a very complex answer beginning with “It depends.” Changing anything in a complex system always leads to multiple interactions and often to unexpected consequences.

Truly qualified ergonomic experts can advise and assist organizations in analyzing their current work setting and making recommendations for improvements. Those recommendations must be based on understanding the functional requirements of the worker in performing his or her tasks and the tools and technologies they employ.

Improvements may be based on changes in the design of work, workflow, operational efficiencies as well as the furniture and configuration of individual and group workplaces.

Finally, ergonomics doesn’t have to cost a lot of money or necessarily involve replacing workplace elements. If done well, ergonomics pays for itself by improving performance, reducing absenteeism, minimizing workers’ health risks.

Generally, applying ergonomics to workplaces involves three stages:

a) Education. Many ergonomic issues are behavioral. One of the difficulties in addressing how people use workplaces is familiarity. The main components of a workplace – chair, desk, computer, etc. are things people use every day. Yet, very often people need to learn how to use these tools and artifacts in ways that are more effective and/or don’t increase the risk of discomfort and possible stress and injury. By launching an education program organizations can raise awareness among the workers and management about the importance of posture; avoiding constrained and stressful positions; starting points for adapting the workplace to the worker, etc.

b) Identification. Once people are aware, they can begin to identify those areas in the workplace that may need attention. Using sound ergonomic information an principles, problems can be classified according to severity and the best ways to address them.

c) Remediation. Some problems will require intervention. This may involve retraining workers how to use devices; adding certain accessories or job aids; or replacing certain elements in the workplace.

Q. In your experience, talk about couple of good projects you have had the privilege of working on with your team. What kind of challenges were you faced with and how did you work to overcome them to create a meaningful solution for your client.

A. As your first question noted, I’ve been around a long time and worked on many great teams with thought leaders in the field. The most successful projects have had several common denominators:

a) A clear and unifying purpose

b) A strong internal champion

c) An involved internal team of influencers representing the wide range of users

d) Commitment to asking the right questions

e) A dedication to doing things right – as well as doing the right things

The other characteristic that has been true of the best projects was our ability to test solutions. From the Sun Microsystems headquarters (A BOSTI project) in the 1980s to the first hotelling project for Ernst and Young in 1990 to a trading floor for Fidelity investments to a complete renovation of a building for Efficient Capital, we worked with the clients to think big, do small and learn fast. What we call rapid prototyping. Workplaces are one of the few designed artifacts that are not tested before rolling them out to the user. Rapid prototyping allows us to try ideas, test solutions and gain valuable feedback to tweak and refine solutions before finalizing them. We also test measures of impact on a small scale. Rapid prototyping allows us to mess with ideas until they work (or they are discarded because they don’t).

The results are multi-fold. Users are engaged in the process and change management is much easier. Change orders are minimized, once the solution is implemented full scale, generating substantial savings. Measures of impact are tested and in place.

leave a comment